This was my first academic article published in a print (!) journal. Reading it now, it displays all of the habits of a budding academic; in fact, it was originally written as a seminar paper during my first quarter in the MA program at UCLA in 2004. It was a “Film and the Other Arts” seminar taught by the legendary Peter Wollen, who I will forever remember for reading to us his extensive lists of films, and for his scribbled notepads which then struck us as idiosyncratic and random, but which I understand now as the intellectual goldmines they are. To get a hold of them today!

Reading the article now, it also feels very 2004, when studies of popular Indian films weren’t as commonplace as they are today. I cringe at my opening line, declared with such naivete! I also cringe at the way that Asian American and South Asian American get conflated, and the way both as viewing subjects get essentialized through my own reading. 2004-05 were years when I was excited by the theoretical prospects of film spectatorship, but when I struggled with “the spectator” as methodology, especially since at this point, my training as a film scholar was primarily in textual analysis so that was my only strategy for studying reception.

Nevertheless, I’m proud of what this article represented at the time. It was my first scholarly attempt to think about Asian and Asian American cinemas together, something I would build upon in later academic papers as well as my dissertation — to say nothing of my work at Pac Arts. The article was published in the Summer 2006 issue of the now-defunct journal Post Script (25.3) for a special issue on Indian Cinema guest edited by David Desser and Frances Gateward.

Mainstream Indian cinema, affectionately known as Bollywood, is no longer a national cinema, but a transnational one, not only in terms of production but in terms of audience. Throughout its history, Bollywood cinema has accumulated fans of various ethnicities from central Asia to Africa, and in recent years has caught the attention of Western viewers and film scholars. Part of this explosion of popularity is due to new venues and technologies for exhibition, such as film festivals, DVDs, and internet piracy, as well as cultural changes such as the acceptance of Indian fashions in Western societies and the adoption of American and European styles in Indian popular culture. However, perhaps the most important reason for the global proliferation of Indian cinema is that South Asians, especially middle to upper class, high-skilled workers, are immigrating to all continents. Generally speaking, this demographic has no desire to cut off its ties with its original culture and thus Bollywood producers and distributors have actively sought to attract this diasporic audience. Compared to its domestic audience, the diasporic market is relatively small, but because of high ticket prices, the profits from a single admission in the United States or Great Britain can equal that of ten tickets in India, so therefore investors are open to breaking the Bollywood narrative tradition of celebrating Indian citizenship to produce works that uphold traditional Indian values in an international, pan-Indian sense. (Dwyer and Patel 216-217) The question of “Indian” identity as represented in new Bollywood films is thus increasingly transnational in outlook, with the meaning of the Non-Resident Indian (NRI) shifting from the villain who needs to be saved from Western corruption to the new Indian aristocrat. Scholars of Indian cinema have already begun to explore how this new conception of the NRI contributes to shifting understandings of Indian nationhood from the point of view of the dominant strain of Bollywood history. However, in this article, I want to consider how Bollywood’s NRI films are understood by NRIs themselves, and how the films construct and contradict diasporic understandings of Indian identity. Diasporic spectatorship of Bollywood films set in cities like New York and London suggests an interesting paradox: on one hand these films are clearly India’s perception of NRIs and thus do not represent any apparent diasporic “reality;” on the other hand they are the only mainstream audiovisual representations of South Asian immigrants available in the mainstream. As a result, these films engage with their overseas consumers as something of a distorted mirror. This article will explore these distortions as well as the special flexibility of Bollywood genre conventions to make such distortions. First I will give an overview of the South Asian film audience in the United States to identify the context of diasporic spectatorship. Then I will briefly survey some ways Bollywood traditions easily accommodate the important new NRI audience. Finally, the bulk of my paper will be a textual analysis of the film Kal Ho Naa Ho (Nikhil Advani, 2003) from the specific point of view of the diasporic audience. My analysis of the film will reveal how the song and dance numbers can be read radically by a diasporic spectator aware of the traditions of musical numbers in Bollywood cinema and Hollywood musicals. I understand that a comparison of these two musical traditions is problematic since the term “musical” refers to the dominant mode of Indian cinema rather than a genre in the Hollywood sense, however my goal is not to equate the two but suggest that the narrative, musical, and visual traditions of both inform the diasporic audience, which as a group with a very special relationship to both India and the United States, is equipped with cultural capital that transcends its race or geography.

Since many of them immigrated to the United States as high-skilled labor, the middle to upper class South Asian communities that settled in places like New York in the last 30 years have had the monetary ability and cultural interest to import Bollywood cinema and maintain theaters and video rental stores in their neighborhoods. Indian cinema scholar Manjunath Pendakur writes, “In the colonial period, when Indian workers migrated to the West or to Africa, they seldom kept in touch with India. . . . A great many of the South Asians who came to North America after 1962, however, had better education and technical skills to attain a higher class position, which enabled them to travel back and forth and stay in touch with India.” (Pendakur 42) Constant contact with the homeland is an important force in keeping interest in Indian cultures alive. In addition, consumption of that culture, be that food, clothing, groceries, television, or cinema, keeps the South Asian American audience informed of what is going on in India, and fill a cultural void threatened by immigration. Prominent scholar Vijay Mishra notes, “In the Indian diaspora video is one of the key markers of leisure activity. . . . It is also a not uncommon method of transmitting cultural events (weddings, anniversaries, even deaths of significant people such as Raj Kapoor) from the homeland to the diaspora or from diaspora to diaspora.” (Mishra 238-239) Therefore video, and now DVD, is widely available to the diasporic audience, often with English subtitles to accommodate younger generations of South Asian Americans. The website indiaplaza.com sells not only Bollywood films but South Asian music, jewelry, groceries, and more. Websites such as panindia.com and IndoFilms.com provide DVD rent-by-mail services to U.S. residents. Bollywood films are of course also available in neighborhoods frequented by South Asian populations such as Queens, New York and Artesia, California. (1) An important phenomenon is the strong presence of movie theaters specializing in first-run Indian films, not just from Bollywood but regional mainstream cinemas as well. New York, California, and New Jersey all have a good number, while Indian movie theaters can also be found in Texas, Illinois, Florida, and Massachusetts. These theaters tend to be located in larger Indian cultural and business centers (“India towns”) so the theater becomes more than a space to see a film, but a space to be Indian. In fact, Indian cricket matches are often projected in Indian movie theaters, turning the space into a place of ethnic pride as well a space to see and hear important news from the homeland. However, the Indian movie theater is no fantasy of Delhi or Calcutta. Although I am sure some audiences go to “lose themselves” in India so to speak, I would imagine that most patrons do not forget the fact that they are in America. Therefore, there is an ironic sense of distanciation from the homeland, the feeling that one is a consumer of India but can never be a producer. This is important in understanding the reception of Bollywood films that are set in the United States; audiences are cognizant of the fact that these images don’t reflect any reality of NRIs, but rather are the reflection of the homeland’s perception of NRIs, and it is through this mind-frame that South Asian Americans interpret the images.

For the film producers, catering to this important diasporic audience by making films with NRI settings easily fits into preexisting traditions of genre, style, and character. First, though the songs now take place in the United States, the musical numbers still adhere to traditional narrative functions. Pendakur identifies six major types of musical numbers in Bollywood cinema: Seesa Padyas, devotional songs, festival songs, romantic songs, night club dances, and songs of pathos. (Pendakur 131-138) The Seesa Padya is sung in mythological battle films and has roots in rural traditions so is not relevant to genres focused on NRIs which are usually urban romances. However in a film like Kal Ho Naa Ho, we encounter the other types. The prayers sung by Naina’s grandmother and her friends is an example of the devotional song (although it is interesting that these devotional song numbers become comical when they are displaced to the United States); the elaborate wedding number “Maahi Ve” is an example of the festival song which propels the family melodrama; the song “Kuch To Hua Hai” is an example of the romantic number; “It’s the Time to Disco” is an example of the night club song; and the title song “Kal Ho Naa Ho” is a definitive example of the song of pathos. Therefore the musical number is flexible enough to be mobilized to fit the new settings and themes. Another convention of the Bollywood musical number is the travelogue, where song and dance take place in a montage of cultural landmarks (often cutting to them without any temporal or spatial logic). In the 90s, the threat of video and satellite forced Bollywood producers to entice local audiences into the theater by increasing production values, and this included the use of as many famous locations as possible. (Ganti 37) Producers often took their crews to Europe, North America, and Africa to achieve this effect. Stories of NRIs obviously fit very naturally into this trend, providing integrated musical numbers with settings in New York (Kal Ho Naa Ho) to throughout Europe (Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge). Linguistic heterogeneity is also an important differentiating element of films about the NRI experience. However, I would argue that the incorporation of English in these films grows out of Bollywood’s long tradition of co-opting other local languages into the dominant Hindi. Jyotika Virdi argues that while Hindi is the official state language, the kind of Hindi used in Bollywood films reflects the Hindi of the streets rather than official institutions, so it has the ability to incorporate other elements, such as Urdu and Sanskrit. (Virdi 18-21) Further, given Britain’s cultural and educational influence on India, both during and after the colonial period, English has always been heard in Bollywood films, and there is even a name, Hinglish, given to the kind of mash of the two languages. Therefore, the combination of English and other Indian languages in films about NRIs derives naturally out of the Bollywood tradition of linguistic flexibility. Finally, while the heavy presence of NRI characters in these films breaks from the traditional themes of nationalism and citizenship, “Indianness” in a vague sense is still evident, if not stronger, in these films. Tejaswini Ganti argues that “since the mid-1990s, Hindi films have frequently represented Indians living abroad as more traditional and culturally authentic than their counterparts in India . . . an authentic ‘Indian’ identity—represented by religious ritual, elaborate weddings, large extended families, respect for parental authority, adherence to norms of female modesty, in junctions against premarital sex, and intense pride and love for India—is mobile and not tied to geography.” (42-43) The figure of the overseas Indian also fits easily into the generic figure of the aristocrat. “Iconic of new wealth the NRI replaces the zamindar (landed wealth) and Kunwar sahibs, scions of the princely states from previous decades, who now stand effaced from popular cinema’s social landscape.” (Virdi 202) So although in the 90s, Bollywood began to produce films with NRI characters, the conventions, types, and styles of Bollywood could easily be tweaked to fit the new settings, languages, and themes.

One such film is Kal Ho Naa Ho, the debut feature of director Nikhil Advani and a production of the Bollywood powerhouse Dharma Productions. The film takes place in New York, and focuses on a love triangle between two MBA students, Naina and Rohit, and a charismatic new neighbor named Aman who has come with his Indian doctor to New York for medical treatment for his chronic heart condition. After Aman moves into the Queens neighborhood, he becomes both a cupid to everyone around as well as the savior of Naina’s family restaurant. Thus New York is depicted in the diasporic Indian imaginary as a city for learning, business, medicine, and romance; Naina and Rohit came to New York for its world-class educational institutions, Rohit’s family came for the opportunity to set up a restaurant, and Aman came for superior medical facilities. That New York is also the space where Aman is able to finally find love is indicative of a romantic ideal of New York, which the film reinforces by the continuous use of distinctive New York locales for settings and “travelogue” montages during musical numbers. In the film’s opening voice-over, Naina narrates that one in four faces in New York is a Hindustani, which refers to a popular idea of pan-“Indianness.” The narration also calls New York “the business capital of the world,” which explains why she and other middle to upper class Indians have chosen to move there. Problems of being an Indian in America are lightly suggested in the opening scenes when Naina complains that the mailman confuses “J. Kapur” with the “J. Kapoor” next door, as well as the utter hate one neighbor feels towards the East Asian restaurateurs who monopolize the neighborhood food industry. Immediately New York is depicted as a city of economic idealism (the title shot centers on the Statue of Liberty and the Chrysler Building) as well as a space of racial conflict, a paradox that seeps into the musical numbers as I will demonstrate below.

Kal Ho Naa Ho was an enormous hit among diasporic audiences. It did well in South Africa and England where it debuted at number six on the British box office charts. In the United States, the film debuted in 52 theaters (mostly in the Indian theaters mentioned above) and for the next 11 weeks, played somewhere in the United States, grossing nearly $2 million in box office sales alone. The film’s $4.2 million box office outside of India made up a third of the film’s overall worldwide theatrical sales. In most diasporic countries, Kal Ho Naa Ho was the year’s highest-grossing Bollywood film. However, what is most interesting to me is that the film was invited to two premier Asian American film festivals in the United States, NAATA’s San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival and Asian Cinevision’s New York Asian American Film Festival where it was the closing night film, partly due to Bollywood’s recent critical vogue among film festival and art house crowds as well the film’s setting and use of NRI themes. Although Kal Ho Naa Ho is not an Asian American production in the traditional sense (its cast and crew are from Bollywood), its appearance in this festival context creates an interesting and complicated viewing situation for Asian American audiences: it is clearly marked as foreign in terms of genre and style yet the context opens the possibility of an Asian American reading which is what I will make in the analyses that follow. The description of the film in the festival programs encourages specific readily-digestible readings, providing a “safe house” for interpretation and cross-cultural consumption. (2) The description of the film on the New York festival’s website describes the film as a “Bollywood-style romp” which suggests that the film is not a Bollywood production, but a diasporic film mobilizing Bollywood tropes such as the musical number, similar to films such as Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding (2001) and Srinivas Krishna’s Masala (1991). The description even notes that the film “reaches out to the India diaspora,” acknowledging that even if it is not an Asian American production, it can be read as an Asian American text. (3) The description in the San Francisco festival’s program also connects the film to American ethnic cinema by comparing the film’s “diasporic multiculturalism” to Spike Lee’s. The most interesting addition is the program’s suggestion that the film can be read as camp, perhaps to appeal to the city’s gay community which had made Dharma Productions’ Kuch Kuch Hota Hai such a hit at the festival the year before. The fact that both Kuch Kuch Hota Hai and Kal Ho Naa Ho played at the city’s extravagant Castro Theatre in the famous Castro District sets the film up for a camp reading. The program notes comment that “all-stars sing, cry, dance and romance their way through New York City to catchy songs and the joyous camp of disco and wedding excess—that rival any Sound of Music sing-along.” (4) The words “disco” and “excess” key in on the film’s camp qualities, and the comparison to the Sound of Music sing-along suggests not only a film style, but a method of spectatorship. I will incorporate camp into my reading of the film, but not from the perspective of the gay spectator, but that of the NRI trying to understand the film’s Bollywood elements in relation to his or her actual experiences living in America.

Through this frame of camp, Kal Ho Naa No’s first musical number, “Pretty Woman,” empowers the NRI reader by opening space for a negotiated reading. The number can be read in terms of utopian multiculturalism and camp to direct diasporic spectators to the ways they have traditionally been excluded from the production of popular culture in America. What immediately strikes the South Asian American audience as particular about the scene is its utopian treatment of race in Queens, New York. According to Madhulika S. Khandelwal, a historian of South Asian immigration, in the 1980s and 1990s, immigrants settled in all neighborhoods of Queens, setting up residence and business in those areas. Instead of isolating themselves in their own corners of Queens, South Asians shared spaces with members of other ethnicities. Khandelwal writes of sites of religious and cultural freedom in Queens:

From one point of view, these spaces can be seen as adding to the rich cultural diversity of Queens. From a different angle, as representations of the continuation of religious traditions that seek to reestablish themselves in a new land, these places of worship stand as symbols of nonassimilable cultures. Individuals wearing traditional Indian dress and pursuing distinct ethnic activities are perceived by many Queens residents as aliens. . . . Many Indian visitors to these places, especially those who stand apart from others because of their dress and other features, have been harassed. Cases of non-Indian violence are not entirely absent in the suburbs, nor are cases of resisting the growth of Indian religious and cultural activities. (188)

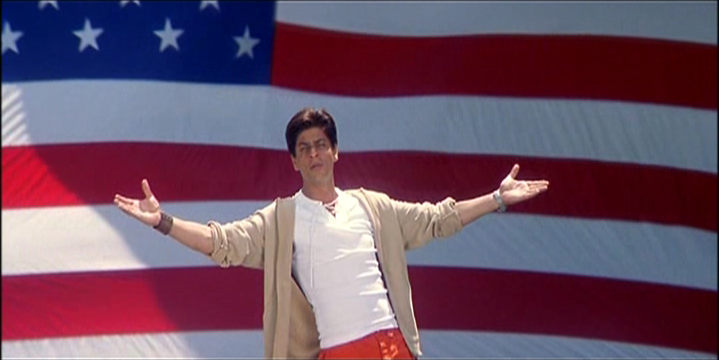

One cultural activity is of course Bollywood cinema, as well as popular Indian dance and music which derive primarily from films. Thus for a South Asian American spectator watching Kal Ho Naa Ho, it is extremely odd to see the dance number where Shah Rukh Khan, the biggest star in Bollywood, leads a swarm of multiracial neighborhood kids in a distinctively Bollywood dance to a translated version of Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman.”  Khan’s character, Aman, literally incites the dance, yelling “Hit it!” to mobilize the street crowd made up of white, black, Hispanic, and East Asian neighbors. In both Bollywood films and American musicals, it is not unusual for background characters to suddenly know all the dance moves as soon as the protagonist draws them into the dance. However, that convention doesn’t easily accommodate a dance which unites a multiracial neighborhood into a lavish Bollywood number, especially given the racial tension that the diasporic audience would be all-too conscious of. Aman is the leader, dancing in front row center, and the background dancers perfectly mimic his every move with huge, unnatural smiles on their faces. While the lyrics are in Hindi, there seems to be no problem with translation; the dancers are hip to the song anyway. In fact, non-Indian characters are often seen strumming electric guitars, obviously “pick-synced” to the prerecorded music track. At one moment in the song, Aman begins to rap the lyrics. For a diasporic spectator this is more than another embarrassing Asian attempt at hipness, but an extremely uncomfortable sight because Aman is rapping in front of black neighbors who seem to have no problem with his imitation of blackness. In fact, the entire scene is predicated on the fact that Aman is all-American, even framing the dance number with a shot of Aman standing before an American flag and a shot of children leaving draped in an American flag after applauding Aman’s performance.

Khan’s character, Aman, literally incites the dance, yelling “Hit it!” to mobilize the street crowd made up of white, black, Hispanic, and East Asian neighbors. In both Bollywood films and American musicals, it is not unusual for background characters to suddenly know all the dance moves as soon as the protagonist draws them into the dance. However, that convention doesn’t easily accommodate a dance which unites a multiracial neighborhood into a lavish Bollywood number, especially given the racial tension that the diasporic audience would be all-too conscious of. Aman is the leader, dancing in front row center, and the background dancers perfectly mimic his every move with huge, unnatural smiles on their faces. While the lyrics are in Hindi, there seems to be no problem with translation; the dancers are hip to the song anyway. In fact, non-Indian characters are often seen strumming electric guitars, obviously “pick-synced” to the prerecorded music track. At one moment in the song, Aman begins to rap the lyrics. For a diasporic spectator this is more than another embarrassing Asian attempt at hipness, but an extremely uncomfortable sight because Aman is rapping in front of black neighbors who seem to have no problem with his imitation of blackness. In fact, the entire scene is predicated on the fact that Aman is all-American, even framing the dance number with a shot of Aman standing before an American flag and a shot of children leaving draped in an American flag after applauding Aman’s performance.  For the American viewer, there is something far too ridiculous about the shot of Aman arms spread in front of Old Glory. Reminiscent of a shot from a patriotic war movie, it is not motivated by any narrative logic (Where does the flag come from? Why is it suddenly behind him? Who is hoisting it up?). For a diasporic audience, it is easy to read this scene as India’s corny utopian vision of what it’s like to be an NRI, complete with multiracial spectacle and a celebration of “India’s new aristocrat’s” fulfillment of the American dream. If we define a camp reading as one which takes a work of art meant to be read straight but is instead read as over-the-top, often in resistance to the intended meaning, the diasporic audience can clearly read this musical number in terms of camp. Granted, with this definition, all Bollywood (and Hollywood musical) scenes potentially could be considered camp, but for the diasporic spectator, this moment is especially excessive and ridiculous given what they know about the “reality” of diasporic life, and the fact that the scene is clearly an outsider’s perspective of America, especially given the context of racial tensions of “brownness” in post 9/11 New York. In talking about the South Asian American film Masala, Jigna Desai writes, “Camp and postcolonial diasporic mimicry become strategies to contest racial, gendered, sexual, and class politics within the film. Therefore, camp can possibly be harnessed to analyze ironic performances of gendered national and racial identities that are connected to a diasporic politics of home and identity.” (Desai 177) Thus an ironic reading of the utopian excess of the scene can see Aman’s attempt at Americanness as an overly optimistic ideal of racial integration, drawing attention to the extent to which such a scene is impossible in the actual streets of Queens. Such an ironic reading of excess would thus empower the diasporic audience by highlighting the tragic rupture between the imagined ideal and reality. The obvious fact that this film was made by an Indian company rather than an American one reminds the audience that this is what the homeland thinks about its “new aristocracy,” drawing attention to the failure of ethnic pride to empower the actual immigrant population. A camp reading can similarly draw attention to the excessiveness and ridiculousness of non-Indians immediately familiar with Bollywood choreography. Whereas one reading may simply label this situation as “unrealistic,” an ironic reading would divorce the scene from any call for realism, and allow the scene to “speak” about the diasporic situation in other ways. The discomfort of seeing such a scene draws attention to the fact that South Asians are not usually accepted as leaders of multi-cultural musical performance, especially in racially tense contexts. Had a black performer led the troupe, the audience would not have had such a reaction because African Americans have traditionally been represented as multi-cultural entertainers in America, a terrain that has excluded South Asians. In American popular culture, black and white entertainers are praised for multi-culturalism when they incorporate Indian culture into their performances (as with Jay-z’s popular remix of Punjabi MC’s Bhangra hit “Mundian to Bach Ke”), but it does not work the other way around. Such distanced, diasporic readings therefore transform a uniquely Bollywood interpretation of South Asian American life into a comment on the way NRIs are racially and culturally “Othered” in places like Queens.

For the American viewer, there is something far too ridiculous about the shot of Aman arms spread in front of Old Glory. Reminiscent of a shot from a patriotic war movie, it is not motivated by any narrative logic (Where does the flag come from? Why is it suddenly behind him? Who is hoisting it up?). For a diasporic audience, it is easy to read this scene as India’s corny utopian vision of what it’s like to be an NRI, complete with multiracial spectacle and a celebration of “India’s new aristocrat’s” fulfillment of the American dream. If we define a camp reading as one which takes a work of art meant to be read straight but is instead read as over-the-top, often in resistance to the intended meaning, the diasporic audience can clearly read this musical number in terms of camp. Granted, with this definition, all Bollywood (and Hollywood musical) scenes potentially could be considered camp, but for the diasporic spectator, this moment is especially excessive and ridiculous given what they know about the “reality” of diasporic life, and the fact that the scene is clearly an outsider’s perspective of America, especially given the context of racial tensions of “brownness” in post 9/11 New York. In talking about the South Asian American film Masala, Jigna Desai writes, “Camp and postcolonial diasporic mimicry become strategies to contest racial, gendered, sexual, and class politics within the film. Therefore, camp can possibly be harnessed to analyze ironic performances of gendered national and racial identities that are connected to a diasporic politics of home and identity.” (Desai 177) Thus an ironic reading of the utopian excess of the scene can see Aman’s attempt at Americanness as an overly optimistic ideal of racial integration, drawing attention to the extent to which such a scene is impossible in the actual streets of Queens. Such an ironic reading of excess would thus empower the diasporic audience by highlighting the tragic rupture between the imagined ideal and reality. The obvious fact that this film was made by an Indian company rather than an American one reminds the audience that this is what the homeland thinks about its “new aristocracy,” drawing attention to the failure of ethnic pride to empower the actual immigrant population. A camp reading can similarly draw attention to the excessiveness and ridiculousness of non-Indians immediately familiar with Bollywood choreography. Whereas one reading may simply label this situation as “unrealistic,” an ironic reading would divorce the scene from any call for realism, and allow the scene to “speak” about the diasporic situation in other ways. The discomfort of seeing such a scene draws attention to the fact that South Asians are not usually accepted as leaders of multi-cultural musical performance, especially in racially tense contexts. Had a black performer led the troupe, the audience would not have had such a reaction because African Americans have traditionally been represented as multi-cultural entertainers in America, a terrain that has excluded South Asians. In American popular culture, black and white entertainers are praised for multi-culturalism when they incorporate Indian culture into their performances (as with Jay-z’s popular remix of Punjabi MC’s Bhangra hit “Mundian to Bach Ke”), but it does not work the other way around. Such distanced, diasporic readings therefore transform a uniquely Bollywood interpretation of South Asian American life into a comment on the way NRIs are racially and culturally “Othered” in places like Queens.

A similar reading of the “It’s the Time to Disco” number exposes the way South Asians are excluded from the production of their own sexual desires as well as their own mastery of American popular culture. As I noted earlier, in American society, an NRI would not be accepted leading non-Indians in American dance, yet a white or black performer dancing Bollywood-style is celebrated as multicultural. The “It’s the Time to Disco” number in Kal Ho Naa Ho however has Naina, Rohit, and Aman leading a Times Square dance club in American disco. Vijay Mishra writes, “The diaspora sees in Western modern dance forms a lack that it wants desperately to correct. Bombay Cinema in turn plays on this lack and supplies it.” (262) In this case, the lack would be not only the ability to demonstrate one’s own mastery of Western dance, but one’s sexual desire in the realm of popular music and dance. Mishra continues, “As to the Bollywood cabarets or modern-day mujras, these become in part diasporic rememorations of an absence of self-representation in the domain of the popular in the nation-states themselves. So while Bombay Cinema incorporates these as an understandable component of diasporic desire, their reception has to be located in the unhappy, schizophrenic, cultural condition of the diaspora.” (266) The lack is especially emphasized in this musical number because the diasporic audience perceives the scene as so over-the-top that the illusion of realism is completely foregone. As in the “Pretty Woman” number, everyone in the club, white or black, magically knows Naina’s moves after she—in Hindi—rushes a white performer offstage and takes charge atop the platform. Of course, the narrative motivation for her actions is that she’s excessively drunk and therefore her ability to lead the group could be due to her sudden courage having just consumed five shots of liquor. However, the fact that her role as leader is so fluidly transferred to Rohit and Aman (and nobody else) during the song suggests that the ability to lead is not simply the consequence of careless intoxication, but is racial.  The other “lack” in mainstream representation that the sequence brings to consciousness is the absolute absence of the (South) Asian heterosexual male sexuality in American culture, especially in terms of the Asian man’s desire for the white and black woman. During the number, Rohit signals a swarm of non-Indian women to dance suggestively with Aman, essentially pimping them to his NRI companion. I cannot detect the narrative motivation for Rohit’s act; to me, it is simply an excessive (in terms of narrative logic) demonstration of sexual desire and sexual power. That the women comply without any resistance is surely idealistic chauvinism, but the discomfort felt by the diasporic spectator doesn’t derive from the misogyny but from the recognition of one’s inability to produce one’s own sexual desires in American popular culture. I am not suggesting that only a diasporic straight man can have such a reaction; a South Asian woman can identify with the sexual desire in terms of race rather than gender. In the director’s commentary to Kal Ho Naa Ho, Nikhil Advani notes that he shot the scene with the intention of making it “hot” like a Beyonce music video, and therefore his mimicry of American popular cultural forms with South Asians as the sexual aggressors is able to communicate to the diasporic audience the extent to which they have been excluded from the production of their own images of desire in American society.

The other “lack” in mainstream representation that the sequence brings to consciousness is the absolute absence of the (South) Asian heterosexual male sexuality in American culture, especially in terms of the Asian man’s desire for the white and black woman. During the number, Rohit signals a swarm of non-Indian women to dance suggestively with Aman, essentially pimping them to his NRI companion. I cannot detect the narrative motivation for Rohit’s act; to me, it is simply an excessive (in terms of narrative logic) demonstration of sexual desire and sexual power. That the women comply without any resistance is surely idealistic chauvinism, but the discomfort felt by the diasporic spectator doesn’t derive from the misogyny but from the recognition of one’s inability to produce one’s own sexual desires in American popular culture. I am not suggesting that only a diasporic straight man can have such a reaction; a South Asian woman can identify with the sexual desire in terms of race rather than gender. In the director’s commentary to Kal Ho Naa Ho, Nikhil Advani notes that he shot the scene with the intention of making it “hot” like a Beyonce music video, and therefore his mimicry of American popular cultural forms with South Asians as the sexual aggressors is able to communicate to the diasporic audience the extent to which they have been excluded from the production of their own images of desire in American society.

The film’s big wedding engagement party musical number, “Maahi Ve,” is, unlike “Pretty Woman” and “It’s the Time to Disco,” actually less radical than is intended, and is perhaps testament to the ways Bollywood conventions reassert certain patriarchal notions of Indian nationalism and heteronormativity. The tensions in the love triangle throughout the film suggest a homosexual pairing between Aman and Rohit, and many of the film’s funniest moments come when they are constantly caught by an elderly Indian woman in inadvertently sexually suggestive poses. However, the “Maahi Ve” sequence turns the homosexuality into an object of mockery, especially with the depiction of the wedding-planner.  During the lavish dance, the elderly Indian woman finally gets to push homosexuality back into the closet by literally pushing the wedding planner out of her way. The sequence also deals with racial heterogeneity through mockery. The engagement of Rohit and Naina is a pairing of a Gujarati and a Punjabi family. While this inter-ethnic coupling is meant to celebrate pan-Indian identity, the depiction of the two groups actually reinforces Punjabi dominance. Mishra writes of the large overseas Punjabi population, “. . . a new Punjabi ethos (Sikh and Hindu) is displacing the old North Indian Hindi ethos of Bombay Cinema. It has been estimated that more than a million Punjabi speakers live abroad with a combined income equal to half the gross national product of the Punjab.” (260) Therefore it is not at all surprising that the film depicts the Gujarati family as silly and musically awkward. Their performance “G-U-J-J-U” is static and laughable (indeed, one Punjabi child chuckles afterwards), while the Punjabi performance of “Maahi Ve” is one of the most lavish, intricately choreographed Bollywood musical numbers I have ever seen. “Maahi Ve” is a celebration of wealth and consumption, with its fetishistic use of color and costumes. While “Maahi Ve” is meant to unite both the Punjabi and the Gujarati families, when Rohit’s parents are seen dancing with the Punjabis, they are still to be read as comical and poor dancers. Thus, the “pan-Indian” identity suggested by the marriage actually reaffirms the dominance of the diasporic audience’s race, which according to Mishra, is likely to be Punjabi. The racial pride of “Maahi Ve” is in sharp contrast with that in the earlier musical numbers whose excessive qualities allowed them to be read ironically. The “Maahi Ve” sequence does not easily lend itself to a camp reading because it is so squarely in the tradition of the Bollywood festival song. In fact, unlike the other musical numbers, “Maahi Ve” takes place in a de-Americanized space. The setting could in fact be India. One would think that NRIs would invite non-Indians to an engagement party but that is not the case here. By stripping the number of any markers of American-ness, the sequence denies the diasporic spectator his or her status in the United States, and worse, suggests that the solution to the narrative must be purely Indian, or in this case, Punjabi.

During the lavish dance, the elderly Indian woman finally gets to push homosexuality back into the closet by literally pushing the wedding planner out of her way. The sequence also deals with racial heterogeneity through mockery. The engagement of Rohit and Naina is a pairing of a Gujarati and a Punjabi family. While this inter-ethnic coupling is meant to celebrate pan-Indian identity, the depiction of the two groups actually reinforces Punjabi dominance. Mishra writes of the large overseas Punjabi population, “. . . a new Punjabi ethos (Sikh and Hindu) is displacing the old North Indian Hindi ethos of Bombay Cinema. It has been estimated that more than a million Punjabi speakers live abroad with a combined income equal to half the gross national product of the Punjab.” (260) Therefore it is not at all surprising that the film depicts the Gujarati family as silly and musically awkward. Their performance “G-U-J-J-U” is static and laughable (indeed, one Punjabi child chuckles afterwards), while the Punjabi performance of “Maahi Ve” is one of the most lavish, intricately choreographed Bollywood musical numbers I have ever seen. “Maahi Ve” is a celebration of wealth and consumption, with its fetishistic use of color and costumes. While “Maahi Ve” is meant to unite both the Punjabi and the Gujarati families, when Rohit’s parents are seen dancing with the Punjabis, they are still to be read as comical and poor dancers. Thus, the “pan-Indian” identity suggested by the marriage actually reaffirms the dominance of the diasporic audience’s race, which according to Mishra, is likely to be Punjabi. The racial pride of “Maahi Ve” is in sharp contrast with that in the earlier musical numbers whose excessive qualities allowed them to be read ironically. The “Maahi Ve” sequence does not easily lend itself to a camp reading because it is so squarely in the tradition of the Bollywood festival song. In fact, unlike the other musical numbers, “Maahi Ve” takes place in a de-Americanized space. The setting could in fact be India. One would think that NRIs would invite non-Indians to an engagement party but that is not the case here. By stripping the number of any markers of American-ness, the sequence denies the diasporic spectator his or her status in the United States, and worse, suggests that the solution to the narrative must be purely Indian, or in this case, Punjabi.

However, the obligations of the Bollywood romantic genre to end with nationalistic pride and heteronormativity do not necessarily deny the diasporic audience of its radical readings of the previous musical numbers, and in fact, the stark difference could potentially reveal certain limitations of the genre for allowing for diasporic readings. While Kal Ho Naa Ho does not articulate a particularly compelling immigrant subjectivity, the viewer is endowed with the ability to read against the text and empower him or herself out of Bollywood’s awkward utopian vision of the NRI experience in Queens. This is possible in large because of the conditions of exhibition spaces in which the film was seen upon release in America: Asian American film festivals, and neighborhoods with large immigrant populations such as Queens, residential and business areas in direct contrast with their representations on the screen. Since programs, including films, shown in Indian movie theaters in the United States are considered transmissions from the homeland, a film like Kal Ho Naa Ho is not mistaken as a diasporic text like those of Mira Nair or Gurinder Chadha. Rather, the film is seen to contain glaring misrepresentations, errors that draw attention not only to the difference between the real Queens and the screen Queens, but the difference between the image of India’s “new aristocrat” back at home and the cruel reality of the NRI in America, a difference that highlights the South Asian American identity as incongruent with images from both India and the United States.

Notes

1 These and other websites are described in Chute, “Deeper into Bollywood.”

2 I take the term “safe house” from Mary Louise Pratt, “Arts of the Contact Zone,” Profession 91 (1991): 33-40.

3 “Tomorrow May Never Come (Kal Ho Naa Ho) program note,” 2004 Asian American Film Festival.

4 “Kal Ho Naa Ho program note,” 2004 San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival program, 30.

Works Cited

Chute, David. “Deeper into Bollywood: Further Research for the Curious,” Film Comment (May-June 2002) http:// http://www.filmlinc.com/fcm/5-6-2002/bollywoodfurther2.htm

Desai, Jigna. Beyond Bollywood: The Cultural Politics of South Asian Diasporic Film. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Dwyer, Rachel and Divia Patel. Cinema India: The Visual Culture of Hindi Film. London: Reaktion Books, 2002): 216-217.

Ganti, Tejaswini. Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Khandelwal, Madhulika S. “Indian Immigrants in Queens. New York City: Patterns of Spatial Concentration and Distribution, 1965-1990,” Nation and Migration: The Politics of Space in the South Asian Diaspora, ed. Peter van der Veer. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1995.

Mishra, Vijay. Bollywood Cinema: Temples of Desire. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Pendakur, Manjunath. Indian Popular Cinema: Industry, Ideology and Consciousness. Cresshill: Hampton Press, 2003.

Virdi, Jyotika. The Cinematic ImagiNation: Indian Popular Films as Social History. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2004.